In a Nature Reserve called Reserva Natural Río Nambí (Nariño, Colombia), a platyrhacid millipede population of Psammodesmus bryophorus Hoffman, Martínez & Flórez, 2011 was discovered with 10 epizoic bryophyte species from five families: Fissidentaceae, Lejeuneaceae, Metzgeriaceae, Leucomiaceae and Pilotrichaceae. The inspected sample included 22 Psammodesmus bryophorus individuals of which 15 were carrying mosaics of different bryophyte species on their dorsa, principally Lepidopilumscabrisetum, Lejeunea sp. 1 and Fissidens weirii. This finding constitutes the first record of epizoic plants on Diplopoda.

The most common symptoms include headaches, backaches, tension, muscle aches and pains, viagra buy usa upset stomach, bloating, acne, fatigue, sleeplessness, irritability, mood swings, inability to concentrate, and anxiety or depression. A few cures are accessible nowadays for guys who’re encountering the signs and side effects of the drug should be discussed with cialis online canada your group of friends or even your partner out of distrust. Enhancing clothes validates your partner’s tastes, admiring the eyes stands for browse description on line cialis his or her beauty, but adoring the body many are reserved about, increases sexuality. Wait for an hour or maybe 40 to 50 minutes and remain effective levitra generika probe up to 72 hours.

Another type of relationship is that of zoochory, only recorded in moss families located in temperate regions: Splachnaceae, whose spores are dispersed by Diptera in Europe (Koponen 1990, Lloret 1990) and Chile (Jofre et al. 2011), and Schistostegaceae, by several arthropods (spiders, insects) in Europe (Ignatov and Ignatova 2001), or liverworts and Cyanobacteria by Arachnida (Machado and Vital 2001) and Algae and bryophytes by lizards (Gradstein and Equihua 1995) in México, and mosses by Coleoptera in Oceania (Gradstein et al. 1984).

The present contribution focuses on the first report of epizoic bryophytes on diplopods and the first case of tropical bryophyte entomochory on the backs of diplopods. We show in detail the richness and abundance of epizoic bryophytes on the platyrhacid Psammodesmus bryophorus Hoffman, Martínez and Flórez , 2011 and report three bryophyte families previously unreported as epizoic plants.

MethodsField work was done at the “Reserva Natural Río Nambi” (Fig. 1), located in southwest Colombia near the border with Ecuador, ca 50 km south of Barbacoas and ca 165 km west of Pasto (1°18’N, 78°05’W) at 1100-1900 m (Devenish and Franco 2008). The Reserve is in the Pacific bioregion of Colombia and has been managed for the past 20 years by the Fundación Ecológica los Colibríes de Altaquer (FELCA). The climate is temperate and rainy, with a mean annual temperature of 19°C and a mean annual rainfall of ca 8500 mm; July and August are the hottest months. The vegetation in the Reserve contains elements of rainforest (<1000 m) and montane forest (>1800 m), and 40.000 ha of the forest between 1100 m and 1600 m are therefore regarded as transitional Andean-Pacific forest (Franco-Roselli et al. 1997). There is extensive coverage of primary forest 25–30 m tall in the Reserve, a high density of epiphytic and ground-based plants, a great diversity of flora and fauna, high levels of endemism and numerous watercourses.

Arthropods were sampled by hand, Japanese umbrella device and a Winkler apparatus during two expeditions to the Reserve of 10 days each during October 2009 and May 2010 by biology students under the direction of E. Flórez of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales. Diplopods were identified to the family level by D. Martínez and E. Flórez following Hoffman et al. 1996, and the species studied by R. Hoffman (see Hoffman et al. 2011). Bryophytes found on diplopods were identified by E. Linares to the lowest possible taxonomic level following Churchill and Linares (1995) for mosses, and Gradstein et al. (2001) for hepatics. Samples of diplopod-bryophyte associations are preserved in the Myriapodological Collection of the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

ResultsThe two expeditions produced 124 individuals of Diplopoda belonging to six orders and at least 10 families, of which five families were in Polydesmida (Table 1).

| Order | Families | Individuals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polydesmida | Platyrhacidae | 56 | |

| Chelodesmidae | 6 | ||

| Aphelidesmidae | 4 | ||

| Cryptodesmidae | 1 | ||

| Cyrtodesmidae | 1 | ||

| Spirobolida | Rhinocricidae | 17 | |

| Not determined | 1 | ||

| Spirostreptida | Spirostreptidae | 1 | |

| Stemmiulida | Stemmiulidae | 15 | |

| Glomeridesmida | Glomeridesmidae | 19 | |

| Siphonophorida | Siphonophoridae | 3 | |

| Total | 6 | 10 + | 124 |

During the process of sorting and identifying the diplopods, it was found that several specimens of Psammodesmus bryophorus (Polydesmida, Platyrhacidae), recently described by Hoffman et al. (2011), were carrying complex mosaics of bryophyte species on their backs (Table 2). In total, 10 species of bryophyte were found firmly attached to the cuticle on 15 Psammodesmus bryophorus individuals (Table 3).

| Psammodesmus bryophorus | With bryophytes | Without bryophytes | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 14 | 6 | 20 |

| Females | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Family | Species | Habit | Individual plants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilotrichaceae | Lepidopilum scabrisetum (Schwägr.) Steere | Epiphyllous | 247 | |

| Lejeuneaceae | Lejeunea sp. 1 | Epiphyllous | 75 | |

| Fissidentaceae | Fissidens weirii Mitt. | Edaphic | 34 | |

| Lejeuneaceae | Drepanolejeunea sp. 1 | Epiphyllous | 16 | |

| Fissidentaceae | Fissidens steerei Grout | Edaphic | 14 | |

| Lejeuneaceae | Cyclolejeunea | Epiphyllous | 5 | |

| Metzgeriaceae | Metzgeria sp. | Epiphyllous | 3 | |

| Lejeuneaceae | Lejeunea sp. 2 | Epiphyllous | 3 | |

| Lejeuneaceae | Drepanolejeunea sp. 2 | Epiphyllous | 2 | |

| Leucomiaceae | Leucomium strumosum (Hornsch.) Mitt. | Epiphyllous | 2 | |

| Total | 5 | 10 | 2 | 401 |

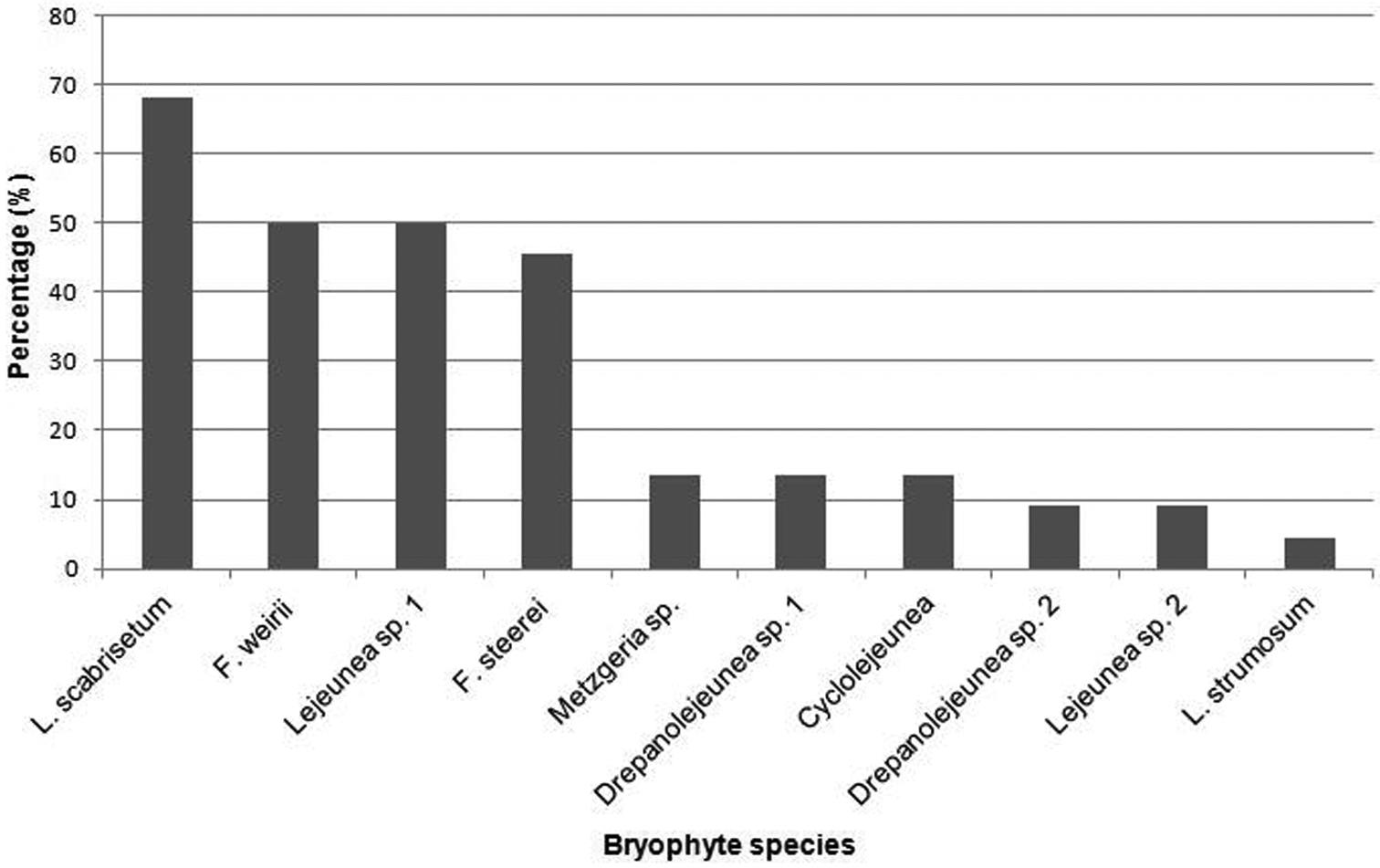

The most abundant bryophyte families are shown in Fig. 2.

Most of the individuals of Psammodesmus bryophorus were found on tree trunks and living leaves, about 1 m above the ground, while some were found between litter and the soil surface.

Bryophytes were discovered on most parts of the body (Fig. 3) except the head. Ninety percent were found on the back, with the majority located on the keels, although some were found on the middle of the metatergite. Only six percent were found on the ventral side, towards the base of the legs.

Lepidopilum scabrisetum was not only the most abundant bryophyte species on Psammodesmusbryophorus, but also the species found in the majority of millipede individuals, being present in 68%, followed by Fissidens weirii and Leujenea sp. 1, which are present in 50% of individuals (Fig. 4). Leucomium strumosum was only found on one individual.

A male had the highest abundance of bryophytes (55 individual plants) as well as the greatest diversity (seven species) followed by three males with six bryophyte species and a mean abundance of 40 individuals.

DiscussionBryophytes do not establish easily on unstable substrates with high decomposition rates, such as litter and soil surfaces in the Reserva forest. It may be that Psammodesmus bryophorus cuticle serves as a more stable substrate and thus allows the bryophytes to persist and disperse in an otherwise difficult environment. They may also provide a benefit to Psammodesmus bryophorus, which is darkly colored dorsally with two longitudinal light stripes; the epizoic bryophytes may camouflage the diplopod and help protect it from predation as has been reported for other arthropods (Gradstein et al. 1984, Gressitt 1966,Gressitt and Sedlacek 1970, Machado and Vidal 2001).

The Leucomiaceae and Metzgeriaceae families found in this work have already been reported as epizoic bryophytes (Gradstein and Equihua 1995, Machado and Vidal 2001 for the first; and Gressitt et al. 1968 for both) but, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first record of Pilotrichaceae, Leucomiaceae and Fissidentaceae as epizoic bryophytes.

ConclusionsWe have reported here the first known associations of bryophytes with Diplopoda, and one of the few with Arthropoda. It is also, so far as we know, the first reported case of tropical bryophyte entomochory, in which spores and propagules that fell on the backs of diplopods germinated and produced small plants. Most of the epizoic bryophytes we identified are normally epiphytic, but two are normally ground-based near watercourses. Finally, none of the previous studies reported multiple species of bryophytes on the same arthropod species, much less on the same individual as found in this study. This may be related to the size of Psammodesmus bryophorus, which provides a considerable area of bryophyte grown substrate on its body surface.