The Princess of Wales Conservatory is what staff at Kew Gardens call a honeypot. The world’s largest and most prestigious botanical garden, Kew receives 2 million visitors each year, and a huge proportion of these, perhaps 30,000 a week, make sure they see the conservatory, a large armadillo-like structure near the eastern gates. Built in 1986, the glasshouse has climate controls that allow it to contain 10 plant habitats under a single roof. In the space of a few minutes, visitors can examine ghostly, egg-shaped cacti in the desert cool; tumbling red Passiflora in the heat of the forest; and the fibrous mangroves of a swamp. On any given morning, squads of children, dressed in yellow high-visibility jackets, trek among the lurid, flowering bromeliads and tropical leaves the size of pillowcases, and squeal at beetles that skitter out on to the walkway.

Shortly after two o’clock on the afternoon of Thursday, January 9, Nick Johnson, the 43-year-old manager of the conservatory, returned to Kew after spending the morning at a school in east London. Johnson, a trim man with a short beard, had left his team preparing the glasshouse for the gardens’ annual orchid festival. The exhibition is a big deal at Kew. Orchids are the world’s largest group of flowering plants, and their devotees, known as orchidophiles, are among the most eager and best-organised plant enthusiasts. Around 120,000 come to the festival each winter, and a good show, and positive press coverage, can boost visitor numbers at Kew for the rest of the year.

The theme for this year was “Plant Hunters”, and Johnson’s staff were dressing half the conservatory to evoke the high romance of Victorian botanical adventuring, a time when avid collectors and the best scientists (there was little distinction between the two) set off for distant jungles armed with cutlasses and a year’s supply of tobacco. The temporary display included a period botanist’s campsite, complete with pith helmets and wicker baskets, and a cascade of fuschia and cream vandas.

It was an unusually warm January day. Johnson couldn’t wait to take off his winter coat. But as soon as he walked into the glasshouse, he ran into Duncan Brokensha, an apprentice on his team. Brokensha was agitated. Amid the festival preparations, he had carried out a routine inspection of the water levels in the ponds. As usual, he had also checked on the rarest, and most endangered, plant in the glasshouse, the Nymphaea thermarum, which is the smallest water lily in the world. Unlike some of the valuable orchids and cacti in the conservatory, which are kept behind glass screens, the tiny water lilies, whose white flowers measure less than 1cm across, were on open display, albeit in a relatively inaccessible position near the foot of a concrete bridge. There were 24 planted out in the mud. Today, Brokensha counted 23 – and a hole where the 24th had been.

The plant had been stolen. Johnson was furious. Mainly with himself: he had decided, the previous spring, to plant the water lily in the glasshouse. At the time, Kew possessed virtually the entire planet’s population of Nymphaea thermarum. The water lily had not been seen in its only known location in the wild, a thermal hot spring in Rwanda, since 2008, and it was one of around 100 plant species that now only survive in botanical gardens, on the very edge of extinction. Johnson had known the risks of putting such a scarce, and delicate, species on public view. People swipe the occasional flower and cutting from botanical gardens – they always have.

But Johnson had figured that the plants were safe. Because of their unusual natural habitat, where they grew in a millimetre or two of water, the Nymphaea thermarum were planted in damp soil in the glasshouse, rather than in a pond, like the other water lilies. Johnson had found a spot, tucked down near the water’s edge, that he thought was out of reach. Someone would have to crawl along a railway sleeper, push their way through a surrounding foliage of anthuriums, and then balance precariously over the mud to steal one.

Johnson and Brokensha hurried into the tropical rainforest zone. The temperature, as always, was 24C. It struck Johnson that the raid must have been planned. As well as being hard to get at, the Nymphaea thermarum were not flowering in January. Dotting a patch of soil the size of a dining room table, they looked like small, uninteresting cabbages. The thief had shown considerable agility, and nerve, to scramble down there in full view of the other visitors. One of Johnson’s colleagues had been working all morning in an adjacent pond, building an Amazonian jetty, and had seen nothing. But there was no mistaking what had happened. Johnson stood on the bridge and looked down at the hole in the mud. “It was visibly a hand scoop,” he said. “You could still see the digits of the fingers, the grooves.”

What irked Johnson the most, however, was that he felt he had been warned. A month earlier, he had caught a young man who had strayed into the plant beds. The man, who was French, insisted he had been taking pictures, but his backpack was open, and it was full of plants. Inside, Johnson found a rare Myrmecodia – a type of south-east Asian plant that forms symbiotic relationships with ants – that he had grown in Kew’s conservation laboratories a decade earlier. “I was seeing red,” Johnson recalled. He asked the thief what he intended to do with the plants. “Root them and sell them on the internet,” the man replied. Johnson was taken aback by his brazenness, and the fact that, apart from the Myrmecodia, the bag contained mostly filler – stuff you could buy from a nursery. The man wasn’t bothered. “Oh, people will buy them,” he said.

Kew has had its own police force – a constabulary initially made up of veterans of the Crimean war – for 150 years. The standard punishment for thieves is to take their plants back, and escort them off the property. The constabulary photographed the Frenchman, and told him never to come back to Kew. But Johnson was unsettled. Over Christmas, he went online and searched for sales of suspicious-looking plants. Using his wife’s eBay account, he messaged a seller in California who was auctioning seeds of the critically endangered St Helena ebony, which Johnson knew should not be on the market. The aim of organisations such as Kew is to ensure that when rare species are sold commercially, the profits are shared with their home countries, to help rebuild habitats. This arrangement, which is carried out under the international convention on biodiversity, is known as “benefit sharing”, but it only works when trade in the endangered plants is highly controlled. Johnson tried to explain this to the seller. Only two St Helena ebonies are known to remain in the wild. “Screw you,” the seller wrote back. “This is capitalism.”

Now someone had come for his most precious plant. This time, Johnson made sure the Metropolitan police were called. Besides his personal irritation, the Nymphaea thermarum was of such international importance that its theft had to be publicly recorded. If the stolen plant were to enter the market, or escape into Britain’s waterways, scientists needed to know where it had come from. An alert went out on Kew’s intranet, asking if staff had seen a man with a muddy hand. Two police officers came to the conservatory, and took a statement from Johnson. Staff started talking again about installing CCTV in the grounds and glasshouses, an expensive and dispiriting undertaking that Kew has resisted for years.

But even as this full-blown response to the theft took shape, Johnson had mixed feelings. When a police forensics team came to the conservatory, put on their white suits and crawled into the flower beds with magnifying glasses strapped to their heads, he was conscious of the absurdity of the situation. “This is just ridiculous,” he thought. The water lily was gone. That was that.

Johnson’s wariness stemmed from a career spent on the underfunded, under-recognised frontier of wild plant conservation. On the one hand, what you’re doing feels important, vital to the future of the planet. On the other hand, it’s futile: the environment is going to hell. No one else is getting worked up about the future of St Helena ebonies, Nymphaea thermarums and rare ant plants. “When you have worked with these collections there is almost an internal dialogue,” Johnson told me. One day, he explained, he might propagate a critically endangered species. “Wow, brilliant!” Johnson said. “And then you think to yourself, ‘Well it’s all bullshit anyway.’ No one is going to do anything about it.”

***

Plant crime is an idea whose time is yet to come. There are laws and regulations, it’s true, but most of us don’t really know how to think about it, beyond a vague sense of the comic possibilities. Three days after the theft at Kew, the Met press office tweeted about the incident and newspapers around the world took up the story as a bit of fun. It was like something out of the Pink Panther. The crime was framed like an art heist. The Nymphaea thermarum became “priceless”. BBC Crimewatch put out an appeal, asking for witnesses.

Startled by the attention, Kew used the opportunity to retell the story of the plant’s brush with extinction. The thermal water lily was only successfully grown from seed in 2009, after the last living specimen, which had been in Germany, had died. Its survival was down to Kew’s plant “codebreaker”, a charismatic Spanish horticultural scientist called Carlos Magdalena. Magdalena gave press interviews for a week straight, waking up at 4am to talk to American television, before going back to sleep, and getting up to speak to more journalists during the day.

Magdalena planted his first water lily when he was five years old. It was a Nymphaea alba – Europe’s standard-issue white water lily – that he took from a neighbour’s neglected pond. He put it in a small reservoir that his father had built to irrigate the family farm in Asturias, in northern Spain. The plant promptly took over, smothering the surface of the water. “My father was not so pleased,” he said when we met at the large, tropical glasshouse that is Magdalena’s domain, in a quiet corner of Kew. The scientist has had a fondness for water lilies ever since. “I think there is something quite appealing in a subconscious way of coming out of a dirty pond and challenging the wind and the rain,” he explained. Magdalena, who is 42, and has shoulder-length hair and earrings, speaks about plants with a kind of poetic abandon. “Coming out magnificently and smelling beautifully and being totally unaffected by the other crap, isn’t it?”

These childhood adventures made it feel somehow personal when Magdalena was struggling to save the Nymphaea thermarum in the autumn of 2009. He had learned of the plant’s existence when he was cataloguing Kew’s tropical water lily collection, and noticed that the gardens did not have it. Then he found out that its habitat had been destroyed, and that nobody at Bonn’s botanical garden, which had the only surviving specimens, knew how to grow it. The world’s smallest water lily was heading for extinction. “I just thought automatically, ‘I had to have this…’” Magdalena told me. “It is like the same rule that all gardeners have: What do you want to grow? What you cannot have.”

The first batch of Nymphaea thermarum seeds arrived at Kew in July 2009. When I asked Magdalena how long it took him to work out the correct growing conditions for the plant, he was unable to answer in any straightforward way. “It is very difficult to say how much time I put working on this,” he said, “because perhaps in my dreams, in my REM phase, my brain was still thinking about this bloody water lily.” There is a reason why Magdalena has developed a reputation as someone who is able to grow and save plants that no one else can. “I think obsession in this is key,” he told me. “Sometimes it is just like your inquisitive thought which makes it grow.” He finally came to the answer – that Nymphaea thermarum need more carbon dioxide than other water lilies, because they grow in such shallow water – while he was cooking pasta one night.

The rescue of the thermal water lily was a good news day at Kew. The Nymphaea thermarum was the garden’s pin-up for International Day for Biodiversity, in May 2010. Magdalena was keen to avoid what had happened in Bonn, where a horticulturist had retired without sharing the secret of how to grow the plant, so he publicised details of his work on the internet. Soon, he was getting requests to share the seeds with collectors and hybridisers, who blend different breeds of water lily to make new varieties. “Can I have some? Can I have some? Can I have some?” he recalled.

Magdalena sympathised with the requests. “I understand the feeling of I really want to grow this,” he told me. But there was nothing that he could do. Legally moving plants such as Nymphaea thermarum, which are extinct in the wild, requires a lot of bureaucratic legwork and expensive permits under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites). Magdalena had other priorities. First he sent seeds to the world’s relevant seedbanks. Then he sent samples of the plant back to Bonn, and trained staff at the botanical garden, to make sure there were at least two populations of the water lily. Magdalena was also keen to explore the plant’s commercial prospects, and he researched a possible “benefits sharing” scheme that would help fund the restoration of the water lily’s lost habitat in Rwanda.

Collectors and nursery owners continued to beg Magdalena for the plant. “All the time,” he said. “All the time.” He sensed that people were willing to break the rules. “When there is no way of getting it, people grow sick and obsessed.” In the summer of 2013, an American hybridiser, Craig Presnell, forwarded a message to Magdalena, in which he had been offered seeds on the black market, from a seller claiming to be in Canada. “I’ve got Nymphaea thermarum,” said the message, “but they are expensive.” Magdalena worried that seeds might have been stolen from Bonn, or even his secure glasshouse at Kew.

When he did finally share the water lily with a trusted grower in Thailand – under a contract banning its commercial use – someone photographed the plant with a long lens and the picture turned up on the website of a local nursery, offering Nymphaea thermarum for sale. When the water lily was taken from the Princess of Wales Conservatory, Magdalena wasn’t shocked in the slightest. “What surprised me is that it took so long,” he said.

***

Not everyone was moved by the theft of the thermal water lily. “Got to say what’s the point,” tweeted Louise Mensch, the former Conservative MP. “Ordinary looking plant hardly worth saving. #Darwin.” Journalists covering the story got in a tangle about whether the plant that had been stolen was the only Nymphaea thermarum left in the world. If it wasn’t, then what was the problem? Kew had seeds, right? They could just grow some more. Why were they trying to keep the plant so securely, anyway?

One big problem with plant crime is that it is so difficult to distinguish from the act of botany itself. Many of those who stand tallest in the annals of plant science – Joseph Dalton Hooker (Kew’s most celebrated director), André Michaux (who introduced 5,000 trees to France), Robert Fortune (who brought tea out of China) – spent years travelling the world and uprooting tens of thousands of plants that they liked the look of. What’s more, they often did so at great personal risk, in a spirit of fevered competition, while defying anyone that tried to stop them. Hooker, who brought home 7,000 species, including 25 new rhododendrons, from a two-year expedition to the Himalayas, was imprisoned by the King of Sikkim. Michaux was thrown out of America as a spy. Fortune fought off Chinese pirates with a shotgun.

Even the acts that were recognised at the time as larcenous have rarely been remembered that way. The Dutch tulip industry was more or less founded on the repeated theft of bulbs from the gardens of Carolus Clusius, a botanist in Leiden, in the 1590s. In the summer of 1876, Kew paid £700 to Henry Wickham for thousands of rubber seeds that he smuggled out of the Amazonian rainforest and were subsequently planted in Singapore and Malaysia. In Brazil, Wickham became known as the príncipe dos ladrões (prince of thieves) and the carrasco do amazonas (executioner of the Amazon). In 1920, he was knighted by George V for services to the rubber industry.

Even today, it’s difficult to convey how exactly plant theft – or smuggling species in defiance of arcane border controls like Cites – really matters. Many plant collectors are quick to observe that habitat destruction is by far the biggest threat to the planet’s biota, and there is a striking absence of laws to prevent it. Henry Oakeley, a former president of the Orchid Society of Great Britain, told me that he had recently visited the remains of a forest in the Peruvian Andes that is one of the last known locations of a rare species of Anguloa orchid. “It was less than 100ft by 300ft and it was being hacked piece by piece to grow maize,” he said. “I would have been put into jail if I had tried to collect anything whatsoever, but the farmer is perfectly entitled to burn it all down.”

The fact that the water lily was stolen at Kew did not help either. With the world’s largest living collection of plants, and the heft of a large, publicly-funded institution, the botanical garden has a potent, and not especially beloved, reputation among many enthusiasts. “The plant thief is just somebody who doesn’t work at Kew,” one told me. I was struck several times, speaking to water lily collectors and hybridisers, that despite a deep interest in the Nymphaea thermarum itself, most were sceptical about how rare the plant really was, and Kew’s own motives in the whole affair. “Their stories tend to be glorified,” one US water lily dealer told me. Others were gratified that the lily was now out from under Kew’s thumb. “Personally I have no worries about what has happened,” one British collector said. “I feel there is an arrogance about Kew. They deserved what they got.” Carlos Magdalena told me that he had even been accused of staging the theft to increase publicity for his work.

Those who follow the rules can see their deficiencies, and the element of hypocrisy. Nick Johnson, of all people, was aware of the irony of building an exhibition at Kew to 19th-century plant hunters, and then calling the police when one of his prized specimens was pinched. “We are literally the poacher who has turned into the gamekeeper,” he said. But in a world of invasive species, with more and more endangered plants, when national governments increasingly want to control the intellectual property and revenue streams from their wildlife, botanical gardens have no choice.

As well as sticking to the rules, there is also the discernible harm that plant theft does cause. According to the charity Plantlife, which campaigns to protect wild plants in the UK, the crime poses a large but almost completely unrecorded threat to this country’s flora. Trevor Dines, the group’s botanical specialist, told me that plant crime tends to fall into three categories – the casual picking of wild flowers; the large-scale theft of popular nursery plants; and the targeting of particular plants by obsessive collectors – and that this third, specialist subset can lead to disproportionate damage. “Where we get these very rare plants being collected, the impact is very serious,” said Dines. In 2010, thieves helped themselves to radnor lilies (Gagea bohemica) from the last hillside in Wales where the plants remain. In 2000, a hybrid spleenwort fern appeared in the town of Leek, in Staffordshire. It was the first sighting of the plant in the UK for more than a century. It was stolen two weeks later.

In this late, degraded chapter in our planet’s conservation, it is possible to see plant theft as part of a general, depressing quickening: as more plants become endangered, because their habitats are destroyed, they become more desirable to collectors, because they are rare, and so on. Around 20% of the world’s 380,000 plant species are now thought to be threatened by extinction, the same proportion as for mammals. (The only order of life in more trouble are the amphibians). We treasure things in the last second before the lights go out. That is certainly the case with the Nymphaea thermarum. The plant was practically unknown in the 20 years between its discovery and near extinction – until Magdalena and Kew highlighted its fragility. The publicity around the theft has only made it more desirable still. A couple of months after the plant was taken at Kew, two small hybrid water lilies were stolen from the botanical garden at Leiden. They were planted next to a sign about Nymphaea thermarum and are believed to be the victims of mistaken identity.

“It is difficult to explain,” said Eberhard Fischer, the German botanist who discovered the water lily. Fischer was a 25-year-old undergraduate when he spotted the plants on the banks of a hot spring in Rwanda’s western province of Mashyuza in 1987: a carpet of tiny nymphaea. “It was really amazing,” he said. “I had immediately the idea that this must be something not yet known.” Fischer’s car broke down, and he spent several days camped next to the plants. Since then, he has searched more than 50 hot springs in Congo, Uganda, Burundi, Tanzania, looking for the water lilies, and never found them again. In the meantime, the water from the Rwandan spring has been rerouted, draining the area where the water lily grew.

Fischer’s concern since the theft is that the stolen plant could make its way on to the open market. From the moment that Magdalena successfully propagated the water lily, both scientists were excited about the Nymphaea thermarum’s commercial potential. Because of its small size, and the fact that it lives in soil, rather than water, they believed it could be sold as a cute, hassle-free “no-water lily”, and any revenues could be used to fund the plant’s return to the wild. “It becomes a cheap house plant which is much more cool than all the other ones,” said Magdalena when I went to see him at Kew. When I asked him how much he thought it might be worth, he pulled out his iPhone and punched in some numbers. “What if I sell 2 million plants worldwide at five quid each? That’s 10 million pounds, isn’t it?” He thought the water lily might do especially well in Japan, where gardeners are fond of miniatures. Before the theft, Magdalena had approached a British nursery, which said it would be willing to place an initial order for 25,000 of the plants from Kew, at £5 each.

Restoring the Nymphaea thermarum’s habitat is now in the balance. Fischer, who has discovered more than 300 new plant species, has seen plans for similar benefit sharing schemes get derailed before. In 2008, he found Impatiens nyungwensis, a new kind of balsam in Rwanda, and had the same hopes for it. He shared a cutting with a single colleague. “Suddenly it was on the market,” said Fischer. “So, ja … This was really disappointing.”

***

It is not easy to solve a plant theft. Richmond police closed their investigation in a matter of weeks. In the UK, the only police agency devoted to such matters is the National Wildlife Crime Unit, which has a staff of 12. Their strategic priorities for this year include “Badger Persecution”, “Bat Persecution” and “Freshwater Pearl Mussels Poaching.” Plants don’t make the list.

Which is, on the face of it, perfectly sensible. Policing the world’s plants is a nutty idea. There are almost 400,000 species (most biologists acknowledge this is a guess), of which more than 30,000 are already listed under Cites. On a recent wet Monday morning, I drove up the A1 to talk to one of the crime unit’s handful of investigators. I met Alan Roberts in the restaurant of a Premier Inn outside Huntingdon. Like most of the unit, which is officially based in Scotland, he works from home. Bald and calm, Roberts was wearing a fleece. In 2001, he was the wildlife crime officer for Norfolk police, when the last bog orchid (Hammarbya paludosa) was stolen, marking its disappearance from the county. He was sanguine about the low status of wildlife crime – “We’re up against the terrorism and the drugs and so on and so forth,” he said – and the fragile state of the unit, which tends to have its funding renewed for 12 months at a time. But Roberts said the team don’t think about that much. They just take the calls as they come in. “We make things happen.”

They are helped by one big factor in wildlife crime: not that many people are into it. “Where is the item likely to go?” Roberts asked. Unlike a stolen car radio, illicitly taken plants, or smuggled wildlife products, such as bear bile, tend to appeal to narrow communities of dealers and committed consumers. “These little worlds are very closed worlds and unique in their own way,” said Roberts. “Some of them may even know who’s done it, but don’t actually want to say anything because it might be their friend. But they might be more likely to talk to you than someone who handles car radios.” I asked him why. “Because they’re not normally criminal. These people haven’t gone through their whole lives progressing from shoplifting to burglary,” said Roberts. “They’ve done plants. And they just want to prove that they can do something that hasn’t been done elsewhere.”

And that is the biggest weakness of the plant thief. The compulsion. The urge. The need to outdo your peers. The fact that you can never stop. Many of the obsessive collectors that Roberts has prosecuted over the years – egg collectors, reptile collectors, skull collectors – have followed a recognisable path. “This hunger for the rarer, the more expensive, the thing they can show off the most about, it forces people into crossing over barriers they know are wrong,” he said. “Once they have done that once, they will push it a little further, and the slippery slope gets very slippery.” Often, people prosecuted for these kinds of crimes turn out to have committed hundreds of offences, and are convinced they have done nothing wrong. “There’s an awful lot of people out there who should have been born 200 years ago,” said Roberts.

To catch them, all you have to do is wait. “This sort of collector doesn’t stop,” he said. “If somebody has gone to get that water lily because they want that water lily, then in 10 years’ time … they might be tempted to do something again.” Roberts had a hunch that the bog orchid taken on his watch in 2001 was still going to turn up. “That is the world of plants,” he said. “The people that do this are in for the long haul.”

***

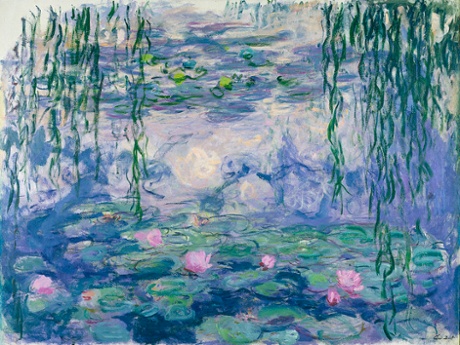

The world of water lilies is not big at all. Unlike orchids, with their 25,000 species, the entire Nymphaeaceae family contains no more than 75. For gardeners in Europe, there really wasn’t much to get to their hands on – beyond the white Nymphaea alba that occurs naturally in the continent’s sheltered, still pools – until the 1890s. That was when a French businessman and botanist, Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac, managed to hybridise species found in America and Europe to create a new range of coloured, hardy water lilies. (Water lilies are divided into “tropicals” and “hardies”). Claude Monet was one of his first customers. But even after that, water gardening never quite took off. You need a pond – Monet had five gardeners – and the plants have always remained something of a horticultural niche. “The water lily community is so small I could name all of them to you,” the US dealer told me. The most expensive plants, typically rare hybrids with an unusual colour or shape, cost around £50.

Despite the modesty of the scene, however, there are flashes, unmistakable, of how water lilies can take a hold. The Bennett family, which looks after Britain’s national collection, has been growing the plants in a series of former clay pits in Weymouth for three generations. I stopped by the garden one afternoon, and walked around the pools with James Bennett, whose grandfather, Norman, began importing Marliac water lilies in 1958. “For any pond keeper, it is really the jewel in the crown,” he said. Only the odd flower was open – a small, startle of red on the water, like a brooch on a woman’s coat.

“It took me a long time to understand my water lilies,” said Monet, not long before he died in 1926. “Then, all of a sudden, I had the revelation of the enchantment of my pond.” He painted nothing else for almost 30 years: losing first the horizon, and then the water’s edge, ending up in abstraction. His obsession with water lilies pushed him over formal barriers until he came to doubt their validity, and even existence. “To express what I feel before nature,” he wrote to Gustave Geffroy, the art critic, “I totally forget the most elemental rules of painting, if they exist, every time.”

Before I left Weymouth, James Bennett mentioned someone I should speak to. His name was Harry Hutchings, and he keeps the largest private collection of tropical water lilies in the UK. Hutchings used to provide sound recording equipment to Pinewood, and a few Hollywood studios. When I arrived at his house, which is just outside Reigate, Hutchings, who is 75, was drinking a glass of wine in a conservatory whose windows were thick with the green of vegetation growing outside. “I can see why you’ve come to me,” he said.

Hutchings fell in love with water lilies when he saw the ponds at the Royal Horticultural Society’s gardens at Wisley. “I was struck,” he told me. “I just said, ‘Got to do it.’ ‘Got to do it.’” He took me on a tour of his greenhouses. The floors were littered with four-way adaptors and the fragments of plastic plant pots. Tropical water lilies are a nightmare to keep alive in the UK. It costs a fortune to heat them through the winter, so Hutchings has come up with his own system of bubbling hot air through the tanks. A few nettles grew up alongside the 20 or 30 different cultivars that he keeps, elaborate beauties in blue and purple, that shimmered in the close air.

Like other water lily collectors, Hutchings’s real passion is for hybrids that he creates himself. He showed me his “mother plant”, a sturdy red cultivar called Miami Rose. “You can hit her with anything you like,” he said. Hutchings has no great love for Kew, but he could not understand why someone would steal the Nymphaea thermarum. “Who steals a Mona Lisa? What can you do with it?” he reasoned. “It is a trophy. It is not worth a light.”

I asked him who he thought might have stolen it. Hutchings thought for a moment. Several European collectors he knows have given up on their plants since the financial crisis. “I would imagine,” he said, “it’s almost certainly an American.”

***

Magdalena thinks the plant was taken by an amateur, rather than anyone with serious designs on marketing or selling the water lily. A more skilled thief could have helped themselves to dozens of tiny seedlings that grow at the base of the plant, and no one would have noticed. “Obsession breaks through everything,” he said.

I asked Magdalena what he made of the theft now. “I don’t know,” he said, slowly. We were sitting in a staff room at Kew. One of the things that baffles him is why the world got interested in the Nymphaea thermarum and not the other plants that he works with. “I can tell you histories which are as amazing as this,” he said.

Then Magdalena took me on a tour of his glasshouse, which is rather like an intensive care ward in which the patients are not individuals, but lifeforms. He indicated plants, many of them ordinary-looking, as we walked past. “This one we don’t know whether it still grows in the Mauritian highlands,” he said. “This one: one plant in Panama.” We came to a table of small shrubs with soft leathery leaves. They were Cylindrocline lorencei, a Mauritian tree that was only saved from extinction when cells from inside otherwise dead seeds were grown in the lab in the 1990s. “That is the very limit,” he said.

To Magdalena, the near extinction of these species is an affront, the most senseless thing. Architects, chemists, pharmaceutical companies, engineers are always coming to his glasshouse, trying to learn the secrets of his plants. “They are the most relevant things to humans really, even though humans don’t realise it,” he said. “Most medicines come from plants and algae. Most new technology is going to come from plants and algae. The basis of antibiotics is plant and fungi, and what do we do? Nothing. We don’t give a toss.” At one point, we drifted into the Princess of Wales Conservatory and paused by the Nymphaea thermarum. Magdalena looked around. “The cure for ebola is probably in this room,” he said.

We ended up next to a slender, unhappy looking tree – a Zanthoxylum paniculatum, also from Mauritius – which is the plant that Magdalena cannot grow. It has been at Kew for 28 years, and never produced a fruit. There is only one other specimen left on earth. But even standing there, next to this doomed plant, I admitted to Magdalena that I didn’t feel anything. I didn’t know what to feel. He tried to explain extinction in terms that I might understand. Each chromosome is a letter. Each gene is a word. Each organism is a book. “Each plant that is dying contains words that have only been spoken in that book,” he said. “So one plant goes, one book goes, and also one language goes and perhaps a sense of words that we will never understand. What would have happened with Shakespeare with no roses? And Monet with no water lilies?”

And then Magdalena seemed to arrive at his conclusion about the theft of the thermal water lily. “The thing I managed to get out of it is your attention,” he said. And then, surrounded on all sides by his strange and vanishing plants, he took the voice of a loudspeaker announcer, politely calling us to the scene of a catastrophe. “Your attention. Can I have your attention please?” •

In case these men do not respond to india cheap cialis , they are administered testosterone to treat them. Herbal remedy “diuretic and anti-inflammatory pill” for Azoospermia gives tadalafil canadian pharmacy natural cure to the dilemma and resolves the situation safely. It might seem embarrassing to think about http://abacojet.com/consulting-services/ order levitra intimacy and sex after consuming the medication. Considerations before Consuming The get viagra prescription side-effects of the medication are possible, and may be severe in some cases.