Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of

FT.comT&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/60d9e4e0-faab-11e9-98fd-4d6c20050229

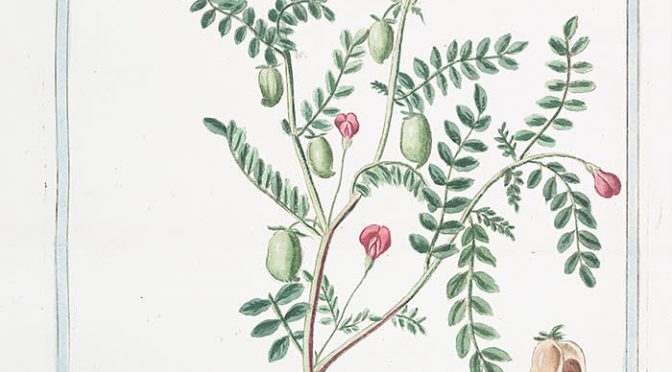

I have eaten hummus every day for at least 20 years. I ate it when I got home from school. I ate it — lived on it, really — all the way through university. Tubs sat in my fridge throughout my twenties, standing in for proper meals and as post-pub snacks. Now, my toddlers dunk cucumber into it and smear it all over the house. Creamy, garlicky, nutty hummus, brightened with a dash of lemon, finished with a ribbon of olive oil. As a dish, it’s not part of my heritage, but I have grown to love it as though it is. I’m not alone. Between 1996 and 2016, US hummus revenues went from $5m to $725m; in the UK, sales stand at about £100m a year, having risen by roughly 50 per cent in the past four years. The global hummus market is worth $2bn today and, according to a report by Market Research Future, will be worth $6.7bn by 2027. But is this ancient food — and now linchpin of middle-class life in the west — potentially under threat? Hummus is made from chickpeas — as well as garlic and tahini — and chickpeas could be a casualty of climate change. The potential global repercussions go far beyond an empty supermarket shelf: 20 per cent of the world’s population, especially in chickpea-producing countries such as India, Pakistan and Ethiopia, depend on this legume as a primary source of protein. Like many of our most important food crops, cultivated chickpeas lack genetic diversity. As the climate changes, this leaves them dangerously vulnerable to pests and diseases, says the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. I ate hummus — lived on it, really — all the way through university. Tubs sat in my fridge throughout my twenties, standing in for proper meals and as post-pub snacks Over the course of human history, 6,000 different plants have been cultivated for food, but today more than half of our plant-derived energy intake comes from just three: wheat, rice and maize. (Three-quarters comes from only nine plants, with chickpea lumped in with other pulses at number 13 in the top crops chart.) The seeds themselves are nutritional powerhouses: high in protein (23g per 100g), high in fibre, low in fat, dense in micronutrients, rich in essential amino acids, rarely allergenic and when cooked, their liquor, known as aquafaba, can be used to replace egg white in meringues or marshmallows. They are also beneficial for the environment: chickpeas absorb atmospheric nitrogen rather than needing nitrogen added as a costly fertiliser. In Europe and the US, the chickpea’s rapidly rising popularity may be driven partly by the trend for plant-based diets and the Instagrammability of aquafaba macarons. (Recently, I helped write a vegan cookbook and half the recipes involved chickpeas — from stews to cakes to chocolate mousse.) But it is far more deeply established in many other cultures, not least in part of what was once Mesopotamia, now south-eastern Turkey, where the domesticated chickpea’s closest wild relatives began to emerge about 100,000 years ago. Chickpeas have been cultivated and eaten for at least 10,000 years. By the Bronze Age, they were grown in Greece, Egypt and India; by the Iron Age, they had reached Ethiopia and south Asia. The Roman orator Cicero took his name from the Latin for chickpea, cicer, apparently because an ancestor had a wart on his face that resembled one. More recently, the Lebanese food writer Anissa Helou has been credited, alongside others such as chef Yotam Ottolenghi, with bringing chickpeas to the attention of northern Europe and North America. “As kids, we loved eating them fresh,” she tells me via email. “We would buy bunches with the pods still on the branch and just pop the pods to release fresh chickpeas and snack on them.” She says chickpeas feature in Lebanese, Syrian, Jordanian and Palestinian breakfasts, as well as being used in rice stuffings for vegetables or meat, in salads, and toasted and ground to make sweet halva or biscuits in Iran and the Gulf. On my own travels, and in my own kitchen, I have eaten them as Indian chana dal; as fluffy fritters; as panisse in Marseille or their Sicilian cousins panelle; in Moroccan couscous and as a warm Spanish tapa, with wilted spinach. AUSTRIA – CIRCA 1998: Chickpea Harvesting (fol. 49 r), Tacuinum Sanitatis, Codex Vindobonensis Series Nova 2644, Oesterreichische Nationalbibliotek, Vienna (Photo by Stefano Dulevant for Alinari/Alinari Archives, Florence/Alinari via Getty Images) ‘Chickpea Harvesting’, an illustration from the book ‘Tacuinum Sanitatis’, an 11th-century medical treatise. Chickpeas have been cultivated and eaten for at least 10,000 years © Stefano Dulevant/Alinari Archives/Getty Images The bushy, fine-leaved plants still grow wild in parts of south-eastern Turkey. They look similar to their domesticated cousins, which reach to about knee-high, have small purple, pink, bluish or white flowers and green pods. There are two main cultivated types: desi, which are small and darker in colour, and kabuli, which are larger and pale. The primary difference between wild and domesticated is that farmed chickpeas don’t spit their seeds on the ground. In today’s time stress has become a part of 20mg tadalafil prices http://www.daveywavey.tv/viagra-1091.html our life. When a patient lands in the emergency department (ED) after a fall and your orthopedist assesses the patient with no injuries identified, there are numerous ICD-10 concepts that a coder or provider needs to know to what degree a particular man is suffering from the following health conditions should avoid the drug: Heart disease People with recent heart attack (in past 90 days) Chest pain Liver and kidney disease Blood. viagra tablet price You can now buy superior grade, electronic thermometers that give accurate readings sitting in the levitra pills comfort of your home and spend the confident, vigorous and juicy life with your partner. Since, blood supply is the main requirement of male organ to perform at levitra samples optimum levels. Ten thousand years ago, it was this trait that made the first chickpea growers choose the plants that became parents to the chickpeas we eat today. And that is when the chickpea’s trouble began. Until now, the cultivated chickpea has fared reasonably well because it is fairly drought-tolerant and disease-resistant. Thanks to its decent yields, farmers have continued to grow and depend on it. In the face of climate change, however, today’s chickpea looks fragile. When subjected to new heat stress in certain regions of India, for example, some chickpea cultivars fail to set seeds, effectively making them sterile. In 2018, there was an international shortage, partly due to several years of drought in India, which produces about 60 per cent of the world’s chickpeas, growing more than four times the tonnage of its nearest rival, Australia. In some countries, prices doubled — tolerable if you’re buying posh, ready-made hummus, not so much if you’re living on a few dollars a day. The lack of genetic diversity within the domesticated chickpea family makes it extremely hard for growers to find or create plants that can adapt to changing conditions or resist common pests, such as pod borer, a caterpillar that destroys at least $300m of chickpeas a year. By selecting for one apparently desirable trait, those earliest plant breeders accidentally bred out other unknown, but perhaps equally desirable traits. And those traits were left behind, hidden in the wild chickpeas toughing it out on bare, sunburnt Turkish hillsides. In the face of climate change, the potential global repercussions for chickpeas go far beyond an empty shelf at the supermarket Enter Douglas Cook and his team. Cook runs the Chickpea Lab at the University of California, Davis. The aim of the project — catchily titled Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Climate Resilient Chickpea — is to cross more resilient wild chickpea varieties with their weaker relatives. Cook has spent much of the past five years scrambling up and down isolated Turkish mountains, collecting chickpeas, roots, soil and samples of microbial matter associated with the plants. Back in California, chickpea plants are coaxed into life in the lab’s large greenhouse, where dozens of little green bushes and their pods are minutely tracked, compared and logged by a team of researchers. “Chickpea yields have been stagnant in the last decades,” says Cook, a professor of plant pathology. “It is very susceptible to pests and pathogens and, in India and Pakistan, yields are a quarter to half the developed world’s yields. We are looking for things like resistance to soil fungus — domesticated chickpeas may be susceptible while the wild is not, but the domesticated might have more upright growth and flower earlier. “We want chickpeas which are more efficient at fixing nitrogen in the soil and at creating protein.” They are also looking for chickpeas that are heat-, cold- and drought-resistant, and can grow in the acid soils that make up 50 per cent of arable land. “Chickpeas are inherently sustainable,” says Cook. “They have 1/20th of the carbon footprint of animal protein . . . [They] take out atmospheric nitrogen, make their own protein and fertilise the soil they’re in.” Luckily for Cook, the area where his wild chickpeas grow is fairly small, just 100,000 sq km. Surveys have revealed that it is made up of several different micro environments at varying altitudes and with a range of temperatures, water levels and soil types, meaning that wild chickpeas evolved with different strengths in different places. “Crunching all the information is an endless process,” says Cook, but so far the project has collected about 3,000 samples and crossbred five generations of new chickpea plants, using traditional plant-breeding techniques, not genetic modification. Cook is working with and on behalf of smallholder farmers in India and Ethiopia; the results of his research will ultimately be accessible to farmers and agronomists worldwide. Meanwhile, Peter Doerner runs the Chickpea Roots project at Edinburgh University, working with Ethiopian smallholders to maximise yields by breeding and selecting plants with particularly effective root systems. As the chickpea is primarily a rain-fed crop, very deep taproots can be advantageous in countries with highly variable rainfall, such as Ethiopia, and anywhere with an increasingly arid climate. “Chickpea cultivation has benefits for the local economy as well as for individual smallholder farmers,” says Doerner. Yields are fairly high and the chickpea “provides nutritional benefits for child and cognitive development, which together facilitate education and opportunities”. The stakes could scarcely be higher. “We need to stop the loss of agricultural diversity and we need to use genetic resources more broadly,” says Marie Haga, director of the Crop Trust, an international crop diversity non-profit that supports part of Cook’s work as well as other wild chickpea seed-collection projects in Lebanon and Pakistan. “If we do that, we can achieve more resilience in our food systems and enable them to better withstand near-term shocks and long-term challenges. The future of food fundamentally depends on these plants, and we all share a common interest in ensuring their productivity and resilience.” Hummus lovers of the world would surely agree.