(Image: AAAS/World Land Trust)

It sounds counterintuitive, but burning oil and planting forests to compensate is more environmentally friendly than burning biofuel. So say scientists who have calculated the difference in net emissions between using land to produce biofuel and the alternative: fuelling cars with gasoline and replanting forests on the land instead.

They recommend governments steer away from biofuel and focus on reforestation and maximising the efficiency of fossil fuels instead.

The reason is that producing biofuel is not a “green process”. It requires tractors and fertilisers and land, all of which means burning fossil fuels to make “green” fuel. In the case of bioethanol produced from corn – an alternative to oil – “it’s essentially a zero-sums game,” says Ghislaine Kieffer, programme manager for Latin America at the International Energy Agency in Paris, France (see Complete carbon footprint of biofuel – or is it?).

What is more, environmentalists have expressed concerns that the growing political backing that biofuel is enjoyingwill mean forests will be chopped down to make room for biofuel crops such as maize and sugarcane. “When you do this, you immediately release between 100 and 200 tonnes of carbon [per hectare],” says Renton Righelato of the World Land Trust, UK, a conservation agency that seeks to preserve rainforests.

Century-long wait

Righelato and Dominick Spracklen of the University of Leeds, UK, calculated how long it would take to compensate for those initial emissions by burning biofuel instead of gasoline. The answer is between 50 and 100 years. “We cannot afford that, in terms of climate change,” says Righelato.

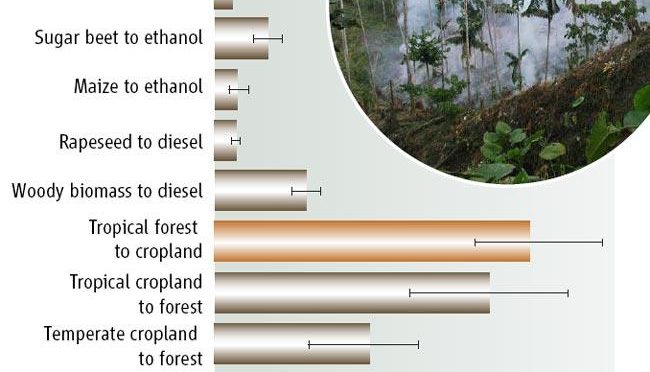

The researchers also compared how much carbon would be stored by replanting forests with how much is saved by burning biofuel grown on the land instead of gasoline.

They found that reforestation would sequester between two and nine times as much carbon over 30 years than would be saved by burning biofuels instead of gasoline (see bar chart, right). “You get far more carbon sequestered by planting forests than you avoid emissions by producing biofuels on the same land,” says Righelato.

He and Spracklen conclude that if the point of biofuels policies is to limit global warming, “policy makers may be better advised in the short term to focus on increasing the efficiency of fossil fuel use, to conserve existing forests and savannahs, and to restore natural forest and grassland habitats on cropland that is not needed for food.”

They do admit, however, that biofuels made from woody materials such as prairie grasses may have an advantage over reforestation – although it is difficult to say for now as such fuels are still in development (see Humble grasses may be the best source of biofuel).

Forests at high latitudes have been found to warm the climate (see Some forests may speed global warming). However, Righelato says this does not affect his calculations as biofuel crops are not, by and large, grown in these areas.

Journal reference: Science (DOI:10.1126/science.1141361)